The Dehumanization of People of Color in Disney and Pixar Films

Disney and Pixar are known as powerhouses in the animation industry, always striving to make the next best animated movie for the world. In recent years, both companies have been trying to be more diverse with their works and started featuring more representations in their films. With films like Pocahontas (1995), Mulan (1998), Moana (2016), and Coco (2017), the companies have started appealing to a wider group of people with these beautiful films. However, some of their representation just seems to fall flat compared to others. Back in 2008, Disney told the world that they were going to have the first ever African American princess in their new movie, The Princess and the Frog. People were ecstatic to finally have a black princess be featured on the big screen and to have a whole new kind of princess to introduce to the new generation. However, it was not until a few months before the release of the movie that it was revealed that Tiana, the princess of the film, would spend most of her time in the film as a frog.

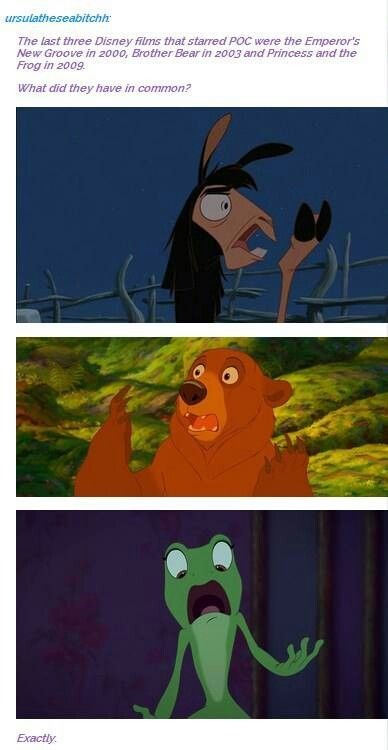

Disney has a little bit of a history of turning POC into some non-human being for most of the film. The Princess and the Frog, Brother Bear (2003), The Emperor’s New Groove (2000), and now Pixar is following in Disney’s footsteps with their new movie, Soul. What is this trope though and why is it harmful? The trope is “an increasingly concerning trope in animation to have main characters who are people of color turned into different animals or beings” and it does not allow these character’s to “learn and grow in their human forms, something white Disney characters are allowed to do” (Jones). By using this trope, Disney and Pixar are dehumanizing these characters and not letting them be shown as their true selves for a duration of the movie. It takes away from the representation that they are claiming to be adding to these films and shows that Disney and Pixar have more work to do to be more inclusive and diverse.

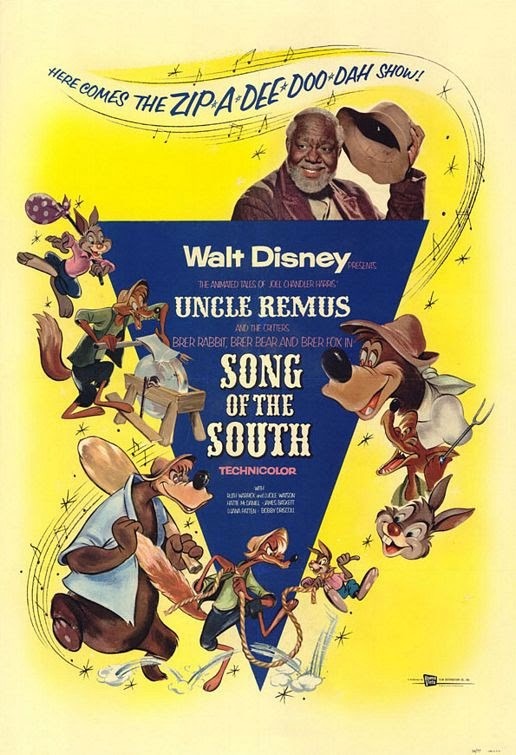

To understand why this trope is hurtful, one must understandDisney and its racist past towards people of color, especially towards black people. Back in 1946, Disney released a live action/animated musical film called Song of the South. The film was based on the stories of the fictional character, Uncle Remus. The character was created by Joel Chandler Harris and was used to tell the struggle the South faced, especially in the plantation post Civil-War. The film follows seven-year-old Johnny during his stay on his grandma’s plantation, where he befriends Uncle Remus, who was a worker on her plantation. During the creation of this film, Walt Disney called on Maurice Rapf to help make this movie as inoffensive as possible to the black community. Rapf warned Disney when he learned about the film that doing anything with Uncle Remus could turn into an “Uncle Tom” stereotype. That comment is what got Rapf the job working on the film, Walt stated that Rapf was “against the black stereotypes,” and would be able to avoid harmful stereotypes. Rapf did his best to remove anything he considered harmful, but he could only do so much for the script. When the movie was released to the public on the 27 of November in 1946, it was met with praise and criticism. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People sent a telegram stating that they “recognizes in Song of the South remarkable artistic merit in the music and in the combination of live actors and the cartoon technique. It regrets, however, that in an effort neither to offend audiences in the north or south, the production helps to perpetuate a dangerously glorified picture of slavery. Making use of the beautiful Uncle Remus folklore, Song of the South unfortunately gives the impression of an idyllic master‐slave relationship which is a distortion of the facts,” (Thomas).

There was a lot of controversy with this movie. Uncle Remus’ character, not knowing if the movie takes place before or after the Civil war, and Brer Rabbit is where most of the controversy started. In original folklore, Brer Rabbit was meant to symbolize oppressed black men “who must use brain rather than brawn to outwit his more powerful masters” (Thomas). However, although Brer Rabbits’ sequences are beautiful and very well animated, the message of his sequences fall a little short. Uncle Remus’ stories in the movie involving Brer shows him wanting to run away from his problems, but the story ends with one cannot run away from their problems and there is no place like home. This would seem like normal lessons, but because of the other controversies in the film and the fact this lesson is combined with a symbol of black men, it is seen as compliance. While it probably was not intentional when making this film, the film still has racist undertones and portrays black people in a certain light that some find offensive.

This is, unfortunately, not the first time this happened with a Disney film. In 1941, Disney released the classic animated film, Dumbo. There were a lot of little things that made Dumbo offensive and racist, but the biggest thing was the crows. The group of crows were deemed as African American stereotypes because of how they talked, how they dressed, and other small mannerisms they had. When the audience meet the crows “they are hanging out and sporting super cool fashion: spats with a vest, pink sunglasses, striped turtlenecks, even enjoying a cigar. Some scholars refer to the lead crow as Jim Crow, though there is no indication that he was named that in the original script nor production notes. However, it was honestly not Dick Huemer’s intention, made evident by how easily he dismissed it when addressed, and I would add that the basis for the critique is not in the characters but the minstrel-style portrayal in the art itself. These crows are all painted the same shade of black; along with their white eyes, this bears a strong resemblance to a minstrel’s black face” (Perea). This was another aspect that seemed to be unintentional by Dick Huemer. He had the leader of the crows voiced by Cliff Edwards, a white man that imitated a Southern African American dialect. Yet, he ensured that the backup crows would be voiced by black voice actors, which was very uncommon at the time. However, “animation that is based on caricaturing as a tactic of representation will have to continuously grapple with whether certain characteristics, racial and otherwise, have been taken ‘too far’” (Barker 483). Huemer might not have had any ill intentions, but it is also hard for an audience to look at the crows today and see anything but a racist caricature. The crows may have been a product of their time, but to say that they were not problematic would be a huge erasure of history from Disney’s past.

People can say that “this was all in the past” and “Disney has moved on from all of these racist caricatures,” but Disney still has a long way to go before they can redeem themselves. The Princess and the Frog seemed like a good way for Disney to redeem themselves and start being not racists, but as I said earlier, their representation in this movie fell a little flat. A “slimy kiss turns Tiana into a frog around thirty minutes into the movie. She hops around for almost an hour before she fully turns back into a human again. When you can consider that the movie runs at 138 minutes, including credits, and that it cuts away to several side plots, this means audiences spend less than half an hour with Tiana appearing as a Black woman” (Tejada). Tiana is barely a person in her own film, barely a princess too, yet Disney claims that this is representation and that it should be enough. Tiana is forced to be closer to her more animal-like nature, just like other princesses of colors in Disney films. Unlike the white Disney princesses, the princesses of color although they “might be lovely and good at heart, they are shown to be closer to expressing their animal natures than white women are. They are therefore unable to fully occupy the performative space of ‘universal humanity’ (and unable to partake in the privileges that accrue to those who occupy that space) in the way that white women can” (Condis 2). Unlike with white princesses, princesses of color are expected to be more rugged and seen as less cultured compared to white counterparts. With Pocahontas, she is more rugged and down to earth because of her native lineage. With Mulan, she is a warrior and must hide her more feminine parts to be a warrior. With Jasmine, she is brash and hardheaded since she refuses to let her father decide her fate. With Tiana, she is a hard worker and stubborn when it comes to achieving her dream. Also, unlike their white counterparts, all these princesses rely heavily on their animal companions to guide them and help them through their journey. The white princesses do have animal companions, but they do not rely on them as heavily as the princesses of color are made to rely on them. Whether unintentionally or intentionally, Disney “invites girls of color to try their luck at adopting a princessly role only to insist that their princesshood be different from the one experienced by white girls. Princesses of color are expected to be more rugged, more earthy, and less cultured and refined than their white counterparts due to their greater degree of animality, their greater kinship to the beast within” (Condis 7). This is not to say that all these princesses aren’t powerful and strong in their own rights. However, it’s just a little strange that only princesses of colors are the ones that must rely more on their animalistic nature throughout their story. It shows the systematic racism that is still in the animation industry, since this keeps happening with princesses of colors while white princesses get to act like normal human beings.

Unlike her other princesses of color, Tiana is not allowed to be a princess of color during her own story. She, along with her love interest, are frogs and during their journey to reclaim their human bodies, and most of the friends they make along the way are animals. This was a first for a Disney princess, since most of the companions a princess meets along the way are human. Not only is Tiana denied being herself throughout her own movie, but she is also denied making new experiences with humans, which goes along with the idea of her being closer to her animalistic nature compared to other princesses before her. Tiana was forced to become a frog against her will, have humanity taken from her for a good portion of her own film, and then not allowed to become friends with other humans for most of her film. The trope of turning people of color prevented Tiana from showing the audience her growth as a black woman. If the audience could watch Tiana growth as a human “it could also give them inspiration and ideas about how to confront and break down walls holding them back in their own lives. But instead of taking the opportunity to educate and enlighten the audience about different ways to beat a stacked system while telling their story, the film’s writers chose to teach us about how much mucus frogs produce. When diverse characters lose their identities, the audience loses opportunities to absorb valuable lessons and insights” (Tejada). Yes, audiences can still learn from Tiana and her growth, even when she is a frog, but the audience is robbed of seeing how people of color resolves issues and grow in an everyday setting.

Instead of learning from Disney’s mistakes, Pixar seems to be repeating them. In Pixar’s newest film, Soul, “which will be the first Pixar film with a black protagonist, the main character turns into a ‘soul,’ presumably for the majority of the film” (Alnic). All the newer trailers for the film show the main character as a “soul,” so it is most likely that the main character will have to learn and grow from his time as a “soul” instead of as a person. This makes the idea of representation a little deceiving, just like with The Princess and the Frog. While this news is heartbreaking, there seems to be a trend with the films that uses the trope of turning people of color into animals; all the people working on these films, producers, writers, directors, etc., are white. Which explains a lot. Although “Soul has a cast of talented black actors, yet most of the top writers, producers, composers, and other people working behind the scenes are white. If there is no diversity in the film’s creation, the film’s true value as representation may be somewhat deceptive” (Alnic). One cannot show proper representation if they have never experienced or lived the representation that they are trying to portray in their story, which is probably why the creators use this trope, since they have no real diversity in the creation of the film, it is easier to create a nonhuman character that anyone could write. It’s one of the reasons why “there is a fear that the animation studios behind those films don’t understand Black characters, and characters of color in general, well enough to imbue them with rich stories. It feels like the characters seemingly have to be transfigured in some form for the writers and animators, mostly white men, to be able to truly care about them” (Jones). It’s why this trope is dehumanizing, and it keeps young generations from seeing themselves on the big screen. By making these movies and not having proper representation, it causes insecurity and makes the younger generation think that there might be something wrong with them if their stories are not being told.

However, companies like Disney and Pixar can continue to get away with this deceiving form of representation, since they are such big companies in the animation industry and have the most control in the industry. They can continue to get away with it, since they know that they will continue to make money from their films, even if they are just giving breadcrumbs of representation in their films. “If companies like Disney don’t acknowledge and change what they have done wrong in the past, they will continue to make the same mistakes in the future. If Disney continues to turn their non-white characters into animals, they will fail to represent those underrepresented groups, which, in turn, influences how future generations will see themselves in society” (Alnic). Until more people call these companies out, they will continue to keep making the same mistakes as they done in the past and fail to properly represent those that barely get to see themselves on the big screen. The only way to stop this from happening is by uniting the people. The people can influence Disney and Pixar into creating what we want to be seen in their films. We might even have a chance to get them to recognize their past racist mistakes with their films, and hopefully improve for the better.

To get proper representation, Disney and Pixar must stop dehumanizing people of color by turning them into non-human things, stop having only white people work on these films, and hire more people that know what these people of color characters are going through. Until more and more people know about this issue in animation, it is just going to keep happening. As I said before, this trope will continue to be harmful “because it’s a trend that has hidden diverse faces, and held back real, meaningful progress when it comes to representation. It’s a trend that has robbed audiences of opportunities to see how minorities face the world and connect with their experiences” (Tejada). We cannot allow it to keep happening if we want to help future generations grow and see themselves being properly represented on the big screen. Every second a person of color spends as a nonhuman being in a film, the audiences will never get to understand what it is like to be a person of color living their everyday lives.

Work Cited

Alnic, Natalie. “Disney- Stop Turning Your Black Characters Into Animals.” Medium, Medium, 20 July 2020.

Barker, Jennifer. “Hollywood, Black Animation, and the Problem of Representation in ‘Little Ol’ Bosko’ and ‘The Princess and the Frog.’” Journal of African American Studies (New Brunswick, N.J.), vol. 14, no. 4, Springer, Dec. 2010, pp. 482–98, doi:10.1007/s12111-010-9136-z.

Condis, Megan. “She Was a Beautiful Girl and All of the Animals Loved Her: Race, the Disney Princesses, and Their Animal Friends.” Gender Forum, no. 55, Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier, Jan. 2015, p. N_A–.

Jones, Monique. “Will Pixar’s ‘Soul’ Be A Repeat Of Racial Tropes?” SHADOW&ACT, 13 Nov. 2019.

Perea, Katia. “Touching Queerness in Disney Films Dumbo and Lilo & Stitch.” Social Sciences (Basel), vol. 7, no. 11, MDPI AG, Nov. 2018, p. 225–, doi:10.3390/socsci7110225

Thomas Inge, M. “Walt Disney’s Song of the South and the Politics of Animation.” Journal of American Culture (Malden, Mass.), vol. 35, no. 3, Wiley Subscription Services, Inc, Sept. 2012, pp. 219–30, doi:10.1111/j.1542734X.2012.00809.x.

Tejada, Andrew. “Representation Without Transformation: Can Hollywood Stop Changing Cartoon Characters of Color?” Tor.com, 16 July 2020.

0 Comments Add a Comment?