New Age for Animation Studios (1950s-1960s)

After WWII, there weren’t many big, animated products that came out in Japan, but that does not mean that animators stopped what they were doing. Animators were working harder than ever to create new animated projects and to try to catch up to the western world of animation. After the war, they were able to create more projects that didn’t focus on Japanese nationalism, so they were able to create any kind of story. This was a time of great change for the industry, animators set out to make it bigger than ever before. Animators wanted to make the industry bigger, to spread their projects across the world, and to change how it was during the war while still providing stories that their people will enjoy. The first step was creating anime studios to help make more animated projects.

Anime studios started popping up all over Japan, one even being created in 1948. That studio was called Japan Animated Films until 1956. Eventually the studio became Tōei Dōga, which is known today as Toei Animation and became part of “Japan’s ‘Big Five’ film studios” (94 Clements). In the present time, this studio is responsible for a bunch of big anime that are beloved all over, they produced One Piece, Dragon Balls Series, Sailor Moon, and many others. Originally, this studio had a goal they wanted to accomplish, a goal that the first president wanted the company to accomplish more than anything. “Ōkawa Hiroshi, the first president of Tōei Studies, founded Tōei Dōga in 1956, with the ambition of creating animated films to rival those of Disney and with an eye to exporting Japanese culture to the world” (66 Lamarre). Hiroshi was inspired by Disney’s Snow White, and he wanted to make a studio that would become “the Disney of the East” (Yasuo).

Tōei Dōga’s first big production was called Hakujaden (The Legend of the White Snake), it was released in 1958 and was the first color anime feature film. To make this film, the studio sent a research team to the US to study Disney’s animation production and even invited several experts from the US to come to Japan to serve as mentors. The film was released in the US in 1961, making it the first anime film to be shown in the US, and due to the success of the film in the US, Tōei decided to release a film yearly. After the success of Hakujaden, the studio decided to produce a new feature film every year, so they got to work on hiring more animators.

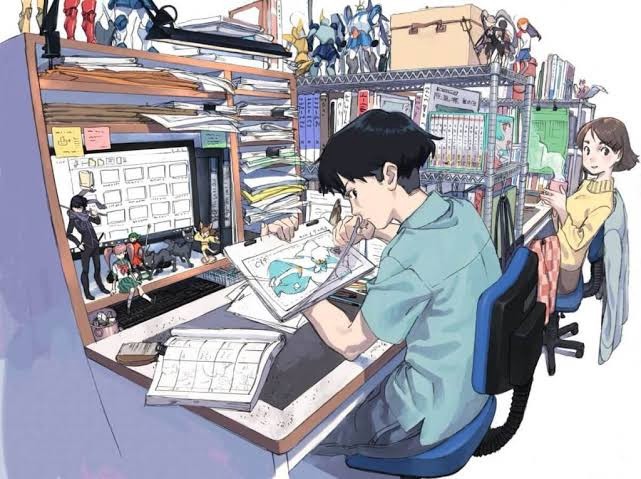

Before going more into the actual anime products that were created at this time, we need to discuss more about what working in this industry was like during the late 1950s into the 1960s. “The animator Okuyama Reiko, who joined Tōei in 1957, observed the wide-ranging differences in pay scales, not only between men and women, but between university graduates and high-school graduates. With Yamamoto Sanae’s ‘60-frames-a-day’ workload understood to be unrealistic, animators were now expected to turn out between fifteen and forty. Okuyama identifies a descending pay scale that implies Tōei ran its animation division as a Japanese conglomerate would run any other manufacturing operation, with ‘company’ men at the top” (Clements 102). The anime industry favored having young men with no family ties work in the industry because then they didn’t have to worry about them trying to make more demands or argue with overtime. At the same time of political unrest in Japan with the Anpo Protests of 1960 (protests of renewing the US-Japan treaty that allowed American troops to remain in Japan), animators fought for Tōei to get a union for all the workers. This was mainly because animators were working long hours and were hardly able to provide for themselves outside of work. “However, it was not until several months later, in September 1961, that negotiations turned hostile. The union demanded an end-of-year bonus of 330 per cent of a normal monthly salary, plus 8,000 yen, amounting to four months’ average pay as a bonus, in keeping with the Japanese norm at the time. The studio countered with an offer 5,000 yen lower. With the studio refusing to budge, the animators held three nominal ‘two-hour strikes’ in early December 1961, and began leafleting passers-by in local shopping streets. The leaflets proclaimed that the harmonious exterior of the animation business belied harsh conditions within, and suggested that the poor pay and harsh hours of the Tōei animators were an infringement of their human rights” (Clements 104). This ended up with the Hiroshi locking animators out of the studio (including locking some union animators in) and cancelled all bonuses on December 5, 1961. The lock down lasted until December 9, 1961, when the studio and the union reached a compromise. The studio agreed to the Unions main demands, but they got to decide the size of bonuses that were given out. However, even with the studio agreeing to unionize, a lot of animators were angry at the studio and left once their contract was up to start their own studios. It may not seem important to know about the work conditions animators went through during this time, but it would be wrong of me to ignore the pain a lot of animators went through in order to create these legendary anime that influenced and inspired the rest of the world. However, even though there was hardship for these animators, some animators went off to create more anime studios, studios that ended up expanding the anime industry.

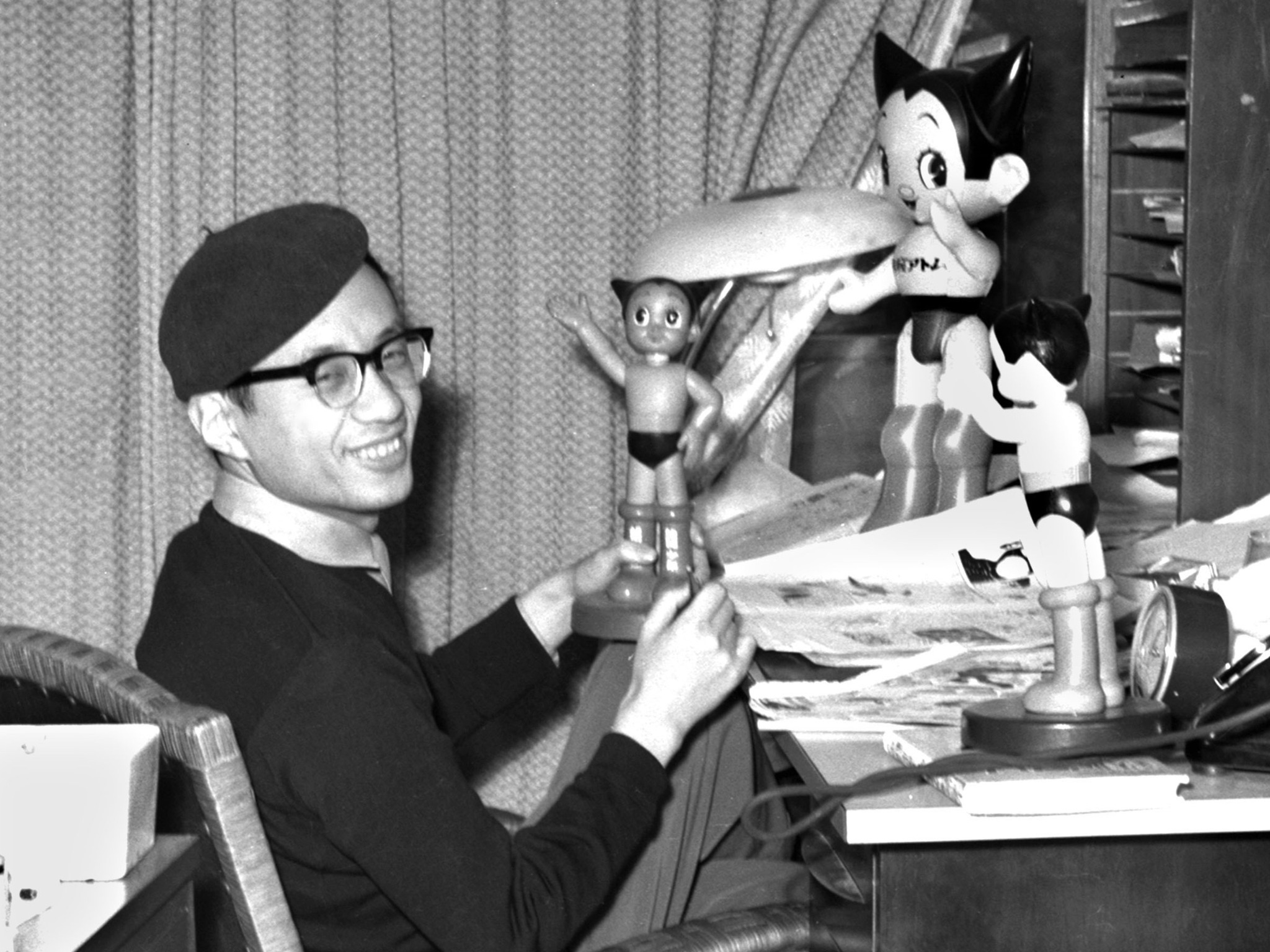

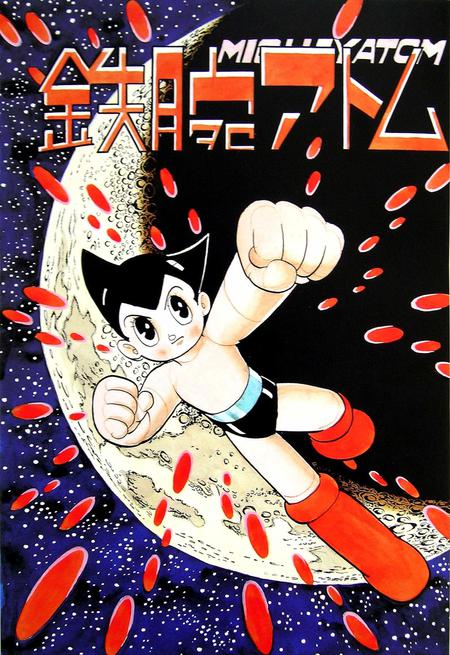

Tezuka Osamu, one of Tōei‘s best animators, left after his contract was up and started his own studio, Mushi Production. At this time, Osamu was a super popular manga artist and earned his respect in the animation industry, so when he started his own studio many of Tōei’s best animators came with him. Tezuka and his studio debuted the first anime TV series that changed the anime industry forever. Tetsuwan Atomu (Astro Boy) debuted on January 1, 1963 and had a different looking animation because of production cost. Mushi Production was a new studio and had very low franchise fees, so the animators “ruthlessly cut the number of drawings, trimmed the number of lines in each image to the bare minimum, and took to using more still images. They worked to make the storyline quicker and devised clever ways of simulating movement, from sound effects to dialogue” (Yasuo). Even with lower production cost, the show became an instant hit in Japan and the US. The how being a hit in the US was a huge thing because “back in the early 1960s, most TV stations in the United States were not even on the air twenty-four hours a day, and the notion of cable TV with hundreds of channels was the stuff of science fiction,” so having a spot for this foreign cartoon on the daily line up was big (7 Drazen). This series brought more anime series to the US and inspired American animation studios to make cartoons with serious storylines, since so many people enjoyed the plot of Tetsuwan Atomu so much.

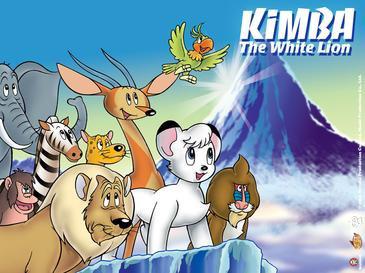

Eventually, Tetsuwan Atomu got sponsored by NBC in America which allowed the show to keep running and they even asked Tezuka to make new shows for the US audience. The new shows would be paid for by NBC and would even be upgraded to color. Mushi Production also adapted Tezuka’s other manga series, Kimba the White Lion,and it made its TV debut on October 6, 1965. A year later, Tōei created the first shojo (female genre targeted at girls between 6 and 15) and magical girl anime in 1966. Sally the Witch aired on December 5, 1966, and it gained popularity throughout several countries. Shojo anime led to many female lead anime being made and expanded the anime industry fanbase. There were several other hits that were produced in the 1960s that changed the anime industry forever, Speed Racer (1967), Princess Knight (1967), Cyborg 009 (1968),Attack No. 1 (1969), and Sazae-san (1969, which is known as the longest running anime series in history currently). Anime was becoming such a huge success overseas, it led to a boom in merchandising for anime series.

However, this success did not last for very long unfortunately.Mushi Production ended up having a hard time with budget issues and soon fell apart after the founder left, leaving the studio to close in 1973. Tōei also faced budget issues with the high production cost, and it ended up with a lot of layoffs in 1972. The anime industry ended up going into a recession around that time, it also didn’t help that the Nixon Shock of 1971 and the 1973 oil crisis was around the same time as the recession. Even though the anime industry was facing hard times at the start of the 1970s, it did not stay that way forever. All this hardship just pushed animators and creators to keep trying to get the world to see their creation. Especially after seeing how much people overseas loved their anime movies and series. This was a time of growth for the industry, it changed a lot since the war, and left the little bubble that formed around the industry when it was first created. Animators and creators would not let a recession stop them from making this industry even bigger.

Work Cited

Anime, -Written by: Right Stuf. “US History Of Anime: A Right Stuf Perspective.” Right Stuf.

Clements J. Anime : a History . Palgrave Macmillan on behalf of the British Film Institute; 2014.

Drazen P. Anime Explosion! : the What? Why? & Wow! of Japanese Animation . Stone Bridge Press; 2003.

Lamarre, Thomas. The Anime Machine: A Media Theory of Animation . University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

Yasuo, Yamaguchi. “The Evolution of the Japanese Anime Industry.” Nippon.com, 30 May 2020.

0 Comments Add a Comment?