The Golden Age of Anime (1970s -1980s)

The 1970’s was a slow start for the anime industry, due to an economic issue caused by the Nixon shock and the oil crisis. Anime studios were closed due to bankruptcy, but out of the ruins of those studios, animators formed new ones, like studio Madhouse and Sunrise. “The 1970s brought changes to the Japanese animation industry at the levels of ownership (sponsors and advertisers), production (animation technology) and access (audiences). Anime became considerably more diverse in the early 1970’s, even as a general recession led all studios to cut back” (Clements 133). The anime industry had to try harder than ever to get viewers invested in their projects, which lead to anime studios coming out with more experimental storylines and debut new directors that went on to change the industry forever.

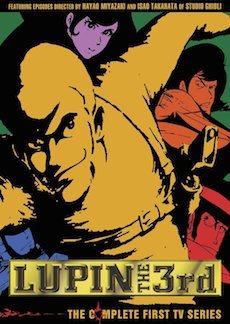

One of the first successful anime to be produced during this time was Tomorrow’s Joe; a boxing anime that came out in 1970 and went on to become an iconic series in Japan and the US. Then, a big franchise was created in 1971, Lupin III Part 1. Although the first part of the series was not that popular, the second series, that came out in the late 1970’s, got the series its fame and it is a successful franchise that is still being made today. The next successful anime that was seen as experimental was Isao Takahata’s series, Heidi, Girl of the Alps, based on the Swiss book, Heidi’s Years of Wandering and Learning. While producers were unsure of the success of this show, since it was a slice of life drama that was aimed toward children and children shows at the time had more exciting plots. Producers’ doubts were pushed aside when the series became an international success, it became especially popular in European countries and in Japan. While this show rose in popularity, sci-fi anime was starting to become very popular, starting with the series, Uchū senkan Yamato (Space Battleship Yamato). This series, released on October 6, 1974, went on to become the first space-opera anime. The series was beloved in Japan because of the mature themes and overarching plot when compared to normal Saturday morning cartoons. In the late 1970’s, the show came to the US with a new name, Star Blazers, the show “was a revelation, since it had a twenty-six- week story-arc, dwarfing its predecessors the way its namesake dwarfed other battleships” (Drazen 8). The series went on to inspire a new wave of sci-fi anime, while inspiring western cartoons to make their storylines a little more mature.

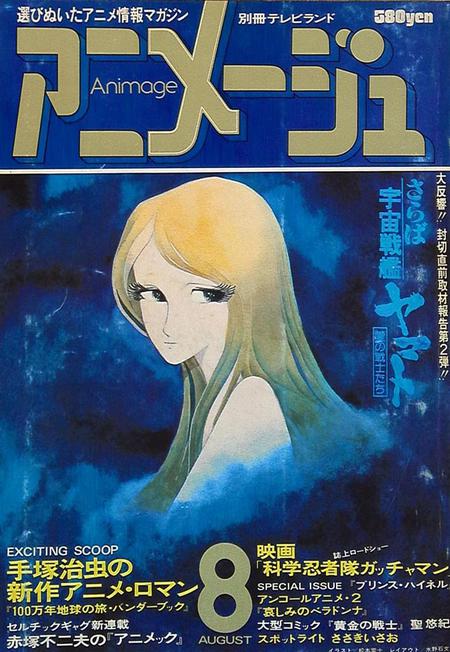

By the late 1970’s, anime was becoming more well known around the world and was seen as a big part of Japanese pop culture. Magazines were being made to provide news and articles about current anime or upcoming anime, the biggest magazine being Animage. Animage was a magazine solely devoted to anime and manga, which provided a safe place for fans to enjoy their hobby and learn more about them. The magazine only came into existence after the series Mobile Suit Gundam was released, the series had a massive fandom, one of the biggest that has ever been in the anime industry at this point. The series came out on April 7, 1979, and it was not even that popular at the start. After the series was first aired, Bandai bought the merchandising rights for the series, and they started to sell model kits of the Gundams that were featured in the show. Due to the success of Mobile Suit Gundam, the “1970s saw a rise in the number of anime aimed at middle school students as companies sought to expand the market beyond the grade school kids who had been the major consumers in the past. Powerful giant robots continued to be popular with children. In fact, toy sales were a significant barometer of the success of a giant robot show, as many shows were produced to sell a related line of toys” (MacWilliams 51). The models were a huge hit with all ages throughout Japan and, eventually, the whole world, which encouraged more Gundam series to be made. There has been 70 Gundam series created, several specials and movies, and hundreds of millions of model kits sold. The Gundam series became a pillar in Japanese culture, due to the massive fanbase all over the world, the millions of dollars the series has made, and created the anime genre, Mecha.

“Anime began its recovery and subsequent success in the United States during the 1980s. At the beginning of the new decade, 56% of Japanese television exports were anime. American viewers began to find anime during this time and, since businesses in the United States did not sell these titles, appropriated the videos among themselves through networks of Otaku in fan clubs and, eventually, online communities. Many of these viewers were people who would have seen series such as Astro Boy as children and rediscovered these shows in their adult lives” (Chambers 96). With this new love for anime, western animators started to be influenced by anime and wanted to make more cartoons like anime. For American series, like Voltron or The Transformers, American companies would collaborate with anime studios to create these series, specifically outsourcing with Japanese animators and having them animate for western cartoons. While western cartoons were taking inspiration from anime, anime was becoming more popular than ever with the creation of the home video market. The home video market played a big part in making the anime industry super successful overseas, especially in the US. Original video animation (OVA) was a huge success in the states, especially pornographic anime (hentai). Hentai films were the biggest anime exports to the US during that time. With fans overseas and fans in Japan, the term “otaku” was created to describe anime fans. The term was created in 1983, it was meant to describe fans with an intense passion for anime, and although the term was never supposed to be negative, over time it was used to describe social outcasts. The term was made extremely negative because of Tsutomu Miyazaki, a serial killer that was named “The Otaku Murderer.” Miyazaki killed four young girls, after the murders his apartment was searched and was discovered that he had a large collection of horror and pornographic video tapes. These tapes were confused as anime tapes, which lead to Japanese politicians trying to ban all things anime and manga, but they were extremely unsuccessful in the long run; However, due to the murders, otaku was then used to call anime fans as perverted outcasts and was considered a negative term until 2013.

The concept of otaku was first used in 1983 by a manga named Cute Pie Comics (Manga Burikko). Today it expresses “extreme” fans who do not want to get out of the world created by anime and manga. Otakus are defined as introverted people, with weak social ties and very few friends.80 In Japan, the otaku culture has spread so much that the sociological consequences of this situation are evident in Akihabara (a district famous for selling electronics products in Tokyo). In 2007, Akihabara’s popularity surpassed that of Tokyo Disneyland. Akihabara is home to the otaku. Flooded with anime products, it welcomes foreign tourists to a considerable extent: “A convergence of discursive forces economic and political, cultural and social, domestic and foreign conditioned a “cool” otaku image in Akihabara, which reframed and restricted the possibilities for people gathering there.” Anime series are so influential that fans are even taking it further and seeing anime characters as their friends. Some fans who are seeking spiritual pursuits even base this on anime, seeing the series they admire as a kind of spiritual guide. As a result of this, anime’s (and in conjunction with it, manga’s) ability to affect the masses can be considered to be quite high. The phenomenon that emerged in Japan has spread rapidly throughout the world and has created a new sociology by creating its own societies.

Even thought there was some aversion to anime after the murders, anime still ended up thriving and created anime classics that are still loved to this day. One of those classics was released on March 11, 1984, by Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata. The film was called Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and it was the first film to ever be produced by their new anime studio, Studio Ghibli. The film was a huge success worldwide and it encourage Studio Ghibli to create even more experimental animated projects. Two years later, the Shonen anime (an anime that is targeted mainly towards boys and is very action packed), Dragon Ball, was released for the first time ever. This anime, created by Akira Toriyama, was a huge success worldwide and led to several sequels being created after the success of this series. The series went on to introduce the martial arts genre to anime, which lead to several more anime series, that surrounded martial arts, being created, and inspired more action-packed western cartoons. The last thing to come out the 1980’s, was the cult classic anime film, Akira. At first, the movie was considered a commercial failure because of how poorly it did in Japanese movie theaters, but the movie was a huge success with international fans. The international theatrical release and the VHS released made the film 80 million worldwide, and to this day the film is considered one of the best animated, sci-fi film ever made. However even though the film was a success worldwide and had a big impact on pop culture worldwide, due to the domestic failure of the film with the death of Osamu Tezuka, the anime industry took a break until the 1990’s.

“The ‘long’ 1970s is often regarded as an intermediate period in the history of Japanese animation, separating the initial flourish of television of the 1960s from the sudden expansion of adult-oriented video in the 1980s. However, the apparent lack of incident, implied by the stability and endurance of Sazae-san and seasonal cinema events, belies a fervent series of technical and stylistic developments in the look and content of Japanese animation. The period saw deep changes in methods of production and practices of ownership, which in turn set the scene for what was arguably anime’s greatest transformation, the arrival of commercial videotape in 1983, and its reception by a viewership that had grown up surrounded by the products of the medium now widely known as ‘anime’” (Clements 155). The 1970’s to the 1980’s introduced a new age for anime because of merchandise sales and the import of VHS to other countries, which allowed the creators of anime to take more risks and experiment. By taking these experimental risks, it inspired not only future anime projects, but animated projects all over the world. Anime was beloved worldwide, so creators wanted to create something just like the anime that they came to love through the years. The 1970’s and 1980’s was a time of experimenting, while the 1990’s and onward was a time of admiration to the project before them.

Work Cited

Akbas I. A “Cool’’ Approach to Japanese Foreign Policy: Linking Anime to International Relations. Perceptions (Ankara, Turkey). 2018;23(1):95-120.

Anime, -Written by: Right Stuf. “US History Of Anime: A Right Stuf Perspective.” Right Stuf, www.rightstufanime.com/post/global-history-of-anime.

Chambers, Samantha Nicole Inëz. “Anime: From Cult Following to Pop Culture Phenomenon.” The Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications, vol. 3, no. 2, 2012, pp. 94–101.

Clements J. Anime : a History . Palgrave Macmillan on behalf of the British Film Institute; 2014.

Drazen P. Anime Explosion! : the What? Why? & Wow! of Japanese Animation. Stone Bridge Press; 2003.

Macwilliams MW. Japanese Visual Culture Explorations in the World of Manga and Anime . M.E. Sharpe; 2008.

Yasuo, Yamaguchi. “The Evolution of the Japanese Anime Industry.” Nippon.com, 30 May 2020, www.nippon.com/en/features/h00043/.

0 Comments Add a Comment?